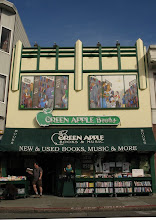

My first visit to Green Apple Books? I remember it well. The creaky floors, Cruddy (by Lynda Barry) on display for $6, and, up on the mezzanine, my favorite section of all - True Crime. As with Mystery and Science Fiction, it is the (hopefully not too) worn and tattered paperback which is the linchpin of this section. Repressing a shriek of delight I grasped Say You Love Satan (David St. Clair) and The Search For The Green River Killer (Carlton Smith). Foolishly I set them down to wander the store some more, then was unable to find the mezzanine again! Years later I was able to read the Carlton book, but St. Clair's renowned work on the hessian Satanic drug addicts of New Jersey continues to elude me.

Eventually I started working at Green Apple, and am known as the store's resident authority on this section, though our bookkeeper is more widely read in this field than me. The dynamics of used true crime had changed in the meanwhile. As I remember the glorious '80s and '90s, every used bookstore was hip deep in trashy, gnarly paperbacks priced under $3. Browse shops in San Francisco these days and these titles are few and far between. So, a few weeks back, when two boxes of of mass market true crime treasure came in across our buy counter, I glimpsed for the first time many titles which captured my attention. Convinced a ravenous market existed for these books, I was determined to read as many as I could before they hit the shelves. Over a period of two weeks, I tore through Angel of Darkness (Dennis McDougal), The Misbegotten Son (Jack Olsen), Freed To Kill (Gera-Lind Kolarik with Wayne Klatt), Ted Bundy: The Killer Next Door (Steven Winn & David Merrill), and The Gainsville Ripper (Mary Ryzuk).

It wasn't all good times. I knew immersion in this level of depravity would have negative effects on my mental health. Children cannot understand that even though a bad thing happened, it is incredibly unlikely to happen to them. After reading true crime for two weeks, I developed this same problem. Before, I was able to control my fear of being abducted and cut up about by realizing, if this terrible thing happens to one person, that's too many, but it does happen. But if it happens in the US to 270 people in one year, the odds of any one individual falling victim is 1 in one million. In practice, even these odds are lessened by my being male, fairly privileged, and avoiding dangerous situations. For example, I do not get hell of wasted drunk, climb in a stranger's car, and take the pills he offers. I don't accept offers to pose naked and tied up for money, even a hundred bucks. This kind of risk reduction has served me well over the years. But logic was defeated after 1500 pages of terrible happenings. The most casual encounters seemed to me to be a set-up. Many men seemed to be hiding a secret and horrifying life. Stopping to tie my shoe, I felt like a limping and lonely antelope on the savannah. While camping, I had to struggle not to run the 50 yards from the river back to our campsite (it looked more like 50 miles) after a branch broke in the distance. I thought it a security breach that my friend told a staggering drunk the name of the campground we were looking for. He seemed an ancillary character, no doubt soon to be picked up by his brother, a maniac with a history of fire-starting and head injuries, recently released from prison...

Plato recommended all things in moderation, but that's not really me. In this instance, I am more like the character sang about by Johnny Cash on Live At San Quentin - "I had all that I wanted of a lot of things I had, and a lot more than I needed of some things that turned out bad." It will be at least ten days before I'm ready for Driven To Kill (Gary King), while Camouflaged Killer (David Gibb) still waits on the shelf at home.

Friday, March 23, 2012

A Time Of Darkness and Despair

Monday, March 19, 2012

A Perfect Tenn

Recently I passed over my pile of new releases to read The Lady of Larkspur Lotion, (1941) from 27 Wagons Full of Cotton and Other Plays by Tennessee Williams, which I purchased for 91 cents at the old 9th Avenue Books years ago. The six-page one-act drama portrays a self-deluded lady who turns tricks in a New Orleans fleabag SRO to pay rent, but thinks she’s a Hapsburg rubber plantation heiress, and who contains many of the archetypal characteristics of all the playwright’s female characters.

My favorite of Tennessee’s outcasts like Sweet Bird of Youth’s lonely, aging film star, Alexandra Del Lago, or Battle of Angel’s ostracized Cassandra Whiteside, refuse to accept personal embarrassment or pity.

Tennessee Williams, (March 26 is the 101st anniversary of his birth), transcended his borderline psychosis by writing five to eight hours per day, seven days a week for 50 years, creating uncompromisingly private plays about public confession that hunger for truth and uphold the sanctity of imagination.

The best art is about art, I've heard, and Tennessee’s poignant art illustrates the victory of fertile and immortal expression, over cold, complex, harsh reality.

A Streetcar Named Desire's Blanche DuBois (whose monologues I have performed in a casual open mic talent show) says “I don’t want realism. I want magic,” summing up my affinity for these vulgar, degenerate, disenfranchised outcasts and the usually male, virile, young wanderers they prey upon, who feel entrapped in scandal, their past catching up with them, who choose the kindness of strangers over commitment to moral principle.

I was introduced to Williams’s decadent and hungry females in a San Francisco State class led by poet and internationally respected Hemingway scholar Robin Gajdusek, in 1992, the final year of his teaching career. In that Tuesday night class I’d feel the fizzy brain high you get listening to a passionate and brilliant lecturer, as Gajdusek revealed Tennessee’s metaphors and themes of Dyonesian ressurrection, illuminating the symbolic pebbles beneath the stream in Williams’s supple ear for gothic-tinged conversation, my wrist aching from furious note-scribbling. When a grandiose student interrupted to opine at tedious length, I’d rage inside, “We’re wasting precious time.”

If I had chosen Beowulf or Dickens to fulfill my single author class requirement, would I be pulling them off the shelf just for fun, 20 years later?

Gajdusek, who died in 2003 at age 78, also wrote Resurrection, A War Journey, recounting fighting with F Company, 37th regiment of the 95th Infantry Division in its assault on a German-occupied fort in Metz, France, 1944, the poetry collection, A Voyager’s Notebook” (1989), and eight other poetry volumes.

Thank you Professor Gajdusek and thank you Tennessee Williams!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)