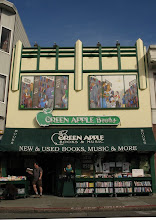

I first discovered Miranda Mellis through her novella The Revisionist -- a poetic, unsettling, gorgeously illustrated tale, and one of those one-sitting reads whose imagery lingers and rattles around the mind for many sittings (walkings, dreamings) thereafter. So I was delighted to pick up her newest collection of similarly fantastic short stories, None of This is Real, and to see that it was published by the tiny local Sidebrow Books, and even more excited to frantically phone in an order for every copy in stock in order to get it in the hands of our Apple-a-Month Club subscribers for April.

Long story short, a tentative but effusive email correspondence ensued, and thanks to Miranda's kindness, local-ness, and professed love for Green Apple, last month we were able to send subscribers an extra special package, which included signed copies of None of This is Real as well as a three page interview with the author herself. Subscribers got first dibs on the hard copy, but here is the interview in its entirety. Welcome to the world of Miranda Mellis -- here lost souls grow strange appendages, a line for coffee becomes a sort of quotidian purgatory, children must contend and compete with the both the failures and the mysticism of their ancestors, and every word is at once startling and perfect. Enjoy.

Green Apple: Hi! What are you reading now?

Miranda Mellis: Right now I am reading The Weather in Proust by Eve Kosovsky Sedgwick; Ugly Feelings by Sianne Ngai; A Year From Monday by John Cage; Debt by David Graeber; The Intuitionist by Colson Whitehead; Best European Fiction 2012 edited by Aleksander Hemon; Culture of One by Alice Notley; The Ravickians by Renee Gladman; and Satan’s Stones by Moniru Ravanipur.

GAB: What were you reading while writing the stories in None Of This Is Real?

MM: I probably can’t do this question justice as the process of finishing these stories unfolded over several years and the reading list would be too long and hard to compile. I will mention a book that is definitely an influence on None of This Is Real and that is Touba and the Meaning of the Night by Iranian author-in-exile Shahrnush Parsipur, who is one of the world’s greatest living novelists but somewhat unknown outside of Iran. Touba, the main character in the novel, is an Iranian woman who longs to become a scholar and mystic but is hampered at every turn by gender oppression. The book spans over 150 years of Iranian history. This book really taught me something I’ll never forget about prophesy, knowledge and power. I urge everyone to seek her out and read her work. Other authors whose work has definitely had an influence on this book are Robert Walser, Bob Glück, and Thalia Field. Kafka, Beckett, and John Cage are constant touchstones.

GAB: Do you bookmark or dog-ear?

MM: I bookmark, dog-ear, annotate, highlight, pencil, pen, sticky and post-it all over my books! They get very collage-d. The day after I got my copy of Ugly Feelings a few weeks ago it was accidentally submerged in a puddle of tea and it immediately swelled up. It was softened by its spill; now it feels more like fabric than paper to the touch. It’s all stained and bloated which seems perfect for what it is exploring, ugly feelings!

GAB: In None of This is Real, the characters are grounded in realistic circumstances which are then turned on their head (or slightly tilted) by the fantastic or surreal. Do you start with the real and imagine ways to undo it or do you approach reality through the lens of the fantastic? Or does your process unfold in a different way?

MM: One definition of the real is that it is a delimitation of that which is legible and perceptible to a given being. That said, perhaps an absurd, extreme, surprising, or improbable metaphor, if it is apt, can work on multiple levels in a way that a more readily expected one may not. {Main character} O’s painful, confusing fin in {the titular story in} None of This Is Real, for example. The fin is real for the protagonist. I imagined the fin as both an adaptation and the onset of a premature reincarnation, and I committed to that conceit, and to that double-meaning, in the writing.

For me, the fact that O can only discover what he is becoming by means of occultists {in the story, O visits a palm reader} describes an epistemological crisis and a kind of political paralysis in the face of the incredible gaps and the outrageously disproportionate distributions of knowledge and agency in a class-based society that protects the rich, and exploits and disenfranchises the rest. The fantastical, or absurd, is in this sense the real, or the everyday, in that our everyday lives are outrageously pressurized in ways that we become habituated to, that become invisible, and then rear up in all sorts of painful intensifications, symptoms and so forth. Forms of magic – magical thinking, magical transformations, and magical actions – represent reachable, alternative forms of agency and knowledge in lieu of political power for the disenfranchised, abandoned, and oppressed, and this often includes children and youth, on whom the stories in this collection are most focused.

By the way, I’m not recommending magical thinking in this book! I’m just trying to think why it becomes a tool and how magic/magical thinking itself in all its complicated manifestations, from manic self-delusions of grandeur, to the clairvoyant, the synchronistic, the Gnostic, and the pagan, becomes useful. I feel dream logic and magic at work in the world, and there is a reason why O gets his information from psychics and books. But it is complicated isn’t it? People turn to prophecy when they feel out of control, when they feel they can’t understand or have a say in their future. What is the difference between seeking prophetic knowledge and seeking political agency? I use the fantastical, the absurd, and the surreal to try to explore the contradictions there.

To your initial question about my approach to the interplay between the fantastical and the real, I can say that I don’t feel bound or beholden by any one genre, but see genre as a tool. What sorts of genres, or time frames, are available to contemporary storytellers to describe the utterly crazy-making conundrums of being a person? For my part, the purely imaginary is part of the real; it seems to me there are many realisms. One can always ask, Whose real? Which one?

GAB: You co-edit a really cool thing called The Encyclopedia Project, described on its website as “part reference book, part literary journal {in the} form of the encyclopedia-from general layout to cross-referencing-as a venue for publishing new, innovative literary works.” What is interesting to you about the form of the encyclopedia, and what do you think is its importance and relevance in what is, for lack of a better/smarter-sounding term for this particular information age, the age of Wikipedia?

MM: The etymology of encyclopedia has to do with expanding circles of knowledge. We’re interested in doing that, and in the idea that a reliable source of information about a given term could come in the form of a story, a lyric essay, a hybrid cross-genre text, or a piece of art, and not solely from scientific, taxonomic, academic lexicons. We’re playing with ideas about canon, knowledge, and expertise, emphasizing the poetic, subjective aesthetics of the encyclopedic form as an expression of knowledge formation. We see the encyclopedia as a horizontal, community art form and knowledge itself as something collectively formed. Pluralism is at the heart of what we’re up to. Wikipedia is also a community-based form for knowledge sharing and acquisition, but our emphasis is on literary art and we’re committed to the print book not just as a fetish (though there is that!) but as an analog, affordable and accessible object that doesn’t rely upon electricity (after its been produced) to be read.

GAB: What encyclopedia entry (one word or phrase) that could go in the upcoming installment of The Encyclopedia Project (which is the letters L-P) would best sum up your current state of mind?

MM: Purposiveness without purpose.

GAB: Everyone´s hollering about the doomed state of the print book these days. Do you buy it? Are these the end times, or just the changing times, and if it´s the latter, what do you think is changing for the kind of writing and publishing you do?

MM: My understanding is that there are more books in print now then ever before. Perhaps over a million books a year are printed. But are there fewer readers? I don’t know. I think the kind of writing and publishing I do is likely to remain marginal, regardless the state of the book, but who knows? Perhaps I’ll accidentally write something popular some day.

GAB: Favorite food in the Inner Richmond?

MM: Burma Superstar!

GAB: If you could have a “staff favorite” on display at Green Apple, what would it be?

MM: I’d vote for the recent reissue of another edition and translation of Women Without Men: A Novel of Modern Iran by Shahrnush Parsipur.

(Note: Thanks to Miranda, we’ve now got both of the Parispur books mentioned in this interview on order for our shelves.)

We are also pleased to be hosting Miranda for a reading along with the incomparable Anna Joy Springer (author of The Vicious Red Relic, Love) at Green Apple on Friday, May 25th at 7:30 PM. Hope to see you there!