Rivka Galchen's debut novel, Atmospheric Disturbances, relates the bleakly hilarious story of Dr. Leo Lebenstein, a man convinced from the first page (the first sentence!) that his wife has been replaced by a very convincing double. His troubled certainty leads him on a quixotic adventure to the literal ends of the earth for the truth behind his wife's disappearance.

Rivka Galchen's debut novel, Atmospheric Disturbances, relates the bleakly hilarious story of Dr. Leo Lebenstein, a man convinced from the first page (the first sentence!) that his wife has been replaced by a very convincing double. His troubled certainty leads him on a quixotic adventure to the literal ends of the earth for the truth behind his wife's disappearance.Atmospheric Disturbances has been critically acclaimed, even by such luminaries James Wood (in the New Yorker), who called the work "an original and sometimes affecting novel, one that knows how to move from the comic to the painful, as the antic twilight of Leo’s insanity gives way to the darkest night."

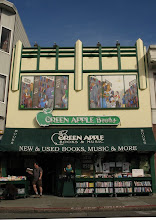

In addition to being a New York Times "Notable Book" of 2008 and earning its author a nomination for the New York Public Library's "Young Lions Award," Atmospheric Disturbances undoubtedly pulled off its greatest laudatory coup by being selected as the Green Apple "Book of the Month" (and the focus of our 2nd Youtube commercial) last July.

Well, okay...

Our selection of the book as our guaranteed book of the month falls slightly below the praise heaped upon it by the higher literary powers, but we're proud of to have helped introduce our customers to the gracious and extremely good-natured Rivka Galchen. We'd like to thank her for taking the time to answer a few questions for the blog!

Green Apple: How do thinking like a novelist and thinking like a scientist differ?

Rivka Galchen: I think novelists perform a kind of dream-work on reality, and scientists a kind of reality-work on dreams. Or maybe the other way around. Depending.

GA: Does thinking scientifically demand that one view the world in an unusual way?

RG: I like to think of all the dilations of scale that happen in science: like geologists seeing ten thousand years as an itty-bitty spot of time, and physicists seeing an atom as a great big enormous thing. It’s like that enormous cherry in the spoon sculpture in Minneapolis by Claes Oldenburg, or those creepy miniature dollhouse works they have at the museum in, is it Philadelphia? Kansas City? Both probably. My husband has long claimed a desire to be a xenobiologist. He’s quite an overachiever in terms of not seeing the world from a traditionally anthropomorphic point of view. He also sometimes wishes he were a machine.

GA: I’m kind of an idiot, so I feel it’s permissible for me to use the parallel worlds theory as an excuse for being late to work. Can you briefly explain the theory in a way that will allow me to sleep in for ten more minutes? In other words, is it possible that my excuse might hold water – in any universe?

RG: Let’s say you have a cat in a box, who either will or will not die of radiation poisoning, depending on whether a certain piece of Radium, say, did or did not decay…and until you open the box to ‘check’, the cat is both alive and dead, each of those outcomes is true, each in their own branching of spacetime, and what’s more important--caring for that cat, or getting to work on time? I think a nice excuse is as good as Basho.

But if someone really wanted to learn something about parallel worlds, and just read something very beautiful, my favorite essay that thinks it through is the late philosopher David Lewis’s “How many lives has Schrödinger’s Cat?” It’s one of the last lecture Lewis ever gave, he knew he was dying of renal failure, and he basically makes this argument for why the immortality seemingly promised by the Many Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics would in fact be, if you follow his logic, tantamount to eternal suffering of unimaginable magnitude. Thus he makes this argument, hoping against immortality. And in this witty, wild, imaginative way. It’s kind of an amazing work.

GA: I read in an interview that you have two enormous photographs of Samuel Beckett in your apartment. Do you often consult with him? If so, what’s the best advice he’s offered?

RG: His hair is so great, and so are his wrinkles, and I know I’ll never be able to pull either off with the same kind of grace. On the cheesy side though: I’m a sucker for his: "Ever tried? Ever failed? No matter. Try again. Fail Again. Fail better."

GA: You seem to express delight in the aesthetic possibilities of certain scientific theories, and in the beauty or weirdness of their elaboration. (As opposed to the actual “truth value” contained within them.) Would you share some of your favorite theories that might not hold scientific weight but that are nonetheless wonderful?

RG: Yes, I’m a fan of the strong misreadings--of interpreting something maybe incorrectly, but in a way that’s interesting all on its own. Like St. Augustine having decided that children chatting a little nursery rhyme—take and read, take and read—were somehow sending him a message to finally accept the bible and become a Christian. As to scientific theories: for cuteness, I’ve never gotten over the theory of phlogiston, nor the plum pudding model of the atom. I’m also a big fan of 1970s quantum mechanics experiments that tried to figure out if the gaze of a dog, or a mouse, had the same effect on an electron as the gaze of a human. But maybe best and most beautiful of all is the paper that the great and persecuted Alan Turing wrote on Artificial Intelligence. He proceeds along forcefully dismissing all known arguments against assuming computers could one day basically have the same intelligence as ‘man.’ (And part of what’s central in his thought experiment is a weird and superfluously gender-bender-y game of pretending to be someone you’re not…it’s a super great paper to read, and can be found here:

So he dismisses pretty much any counterargument you can think of, but then ends by saying: Except for this phenomenon of ESP, which appears to be valid, and which, if it is, might topple all of our assumptions.

GA: I apologize for this sounding like it needs a punchline, but how are love and the weather alike?

RG: Sublime disasters? Also ordinariness? Incredibly predictable in a general way, and hopelessly uncertain in any given situation? I feel somehow embarrassed now, having said any of this!

GA: Were you consciously led to Leo Liebenstein or did he just appear, demanding a starring role?

RG: He came to me talking like turn of the century german Romantic. I told his agent I saw real potential in him, but also that he’d have to learn to ham it up, be nice to the midgets, and that also he’d need to put on a good twenty pounds. Also Nicholas Cage backed out of the contract. The midgets—we ended up cutting, it was seen as too Willow-y a move. Leo and I came to really respect one another, but it never became social.

GA: What is the best thing about having written a novel?

RG: Mailing it to my incredibly great high school English teacher. I’m such a nerd. I’m sure she has plenty of other stuff to read.

GA: And now some seemingly easy questions that promise to provide a glimpse into Who You Are, but really don’t reveal very much at all. Dostoevsky or Tolstoy?

RG: Maybe if Tolstoy had had a tremendous gambling debt, he could have been as good.

GA: Hardcover or paperback?

RG: Definitely paperback. But even better: tiny little paperbacks, like those pocket book sized books they make in Japan for taking on the train. Tiny, tiny, and with a cardstock little cover.

GA: Susskind or Hawking?

RG: It’s hard not to love best a physicist from the South Bronx.

GA: Late night or early morning?

RG: Early is like heaven. No one talks.

GA: Do you have a favorite rainy day book?

RG: Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton and Edwin B. Mullhouse; The Life and Death of an American Writer (1943-1954) by Jeffrey Cartwright by Steven Milhauser.

GA: What are you currently reading?

RG: James Tiptree, Jr: the Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon by Julie Phillips and Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye.

GA: What is a book that you feel not enough people know about?

RG: Anything by Jane Bowles. Especially Two Serious Ladies, A Better Angel by Chris Adrian, and The Horned Man by James Lasdun.

GA: I want to conclude the interview with a nod (ahem!) to Green Apple Books: Suppose you were forced to pick a favorite bookstore you’d never been to. Which bookstore might that be?

RG: The one that hides in a labyrinth of unnamed Chinese shops.

1 comment:

Enquiring minds need to know: was Sparks wearing his blazer for this interview?

Post a Comment